The following is part of a presentation given at the American Legion by Post Historian Rob Smith on November 11, 2017.

In the United States, November 11 is, of course, Veterans Day but, prior to 1954, it was known as Armistice Day as it marks the anniversary of the end of World War I. In 1918, fighting formally ended at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month when the Armistice with Germany went into effect.

It was the day the “War to End All Wars” ended and spontaneous celebrations took place from coast to coast in America. In Cedar Rapids, 10,000 people took to the streets on the 11th and marched around the city shouting, honking horns and cheering endless hurrahs. It was a moment of unrestrained joy around the globe.

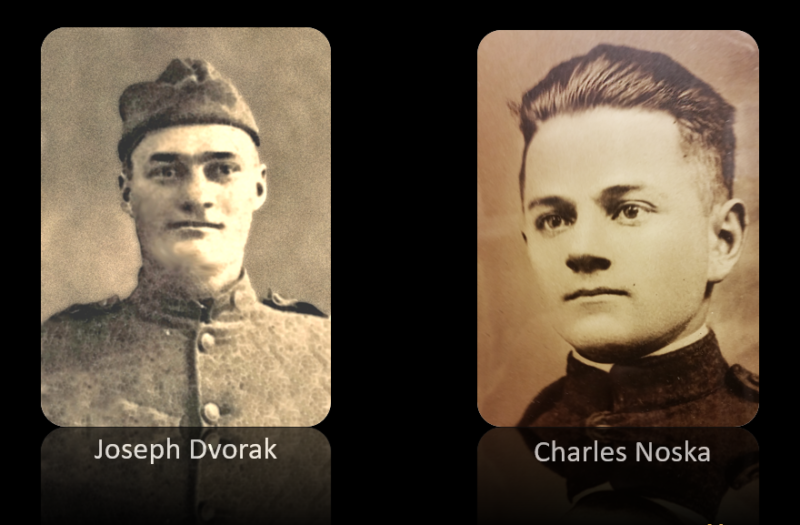

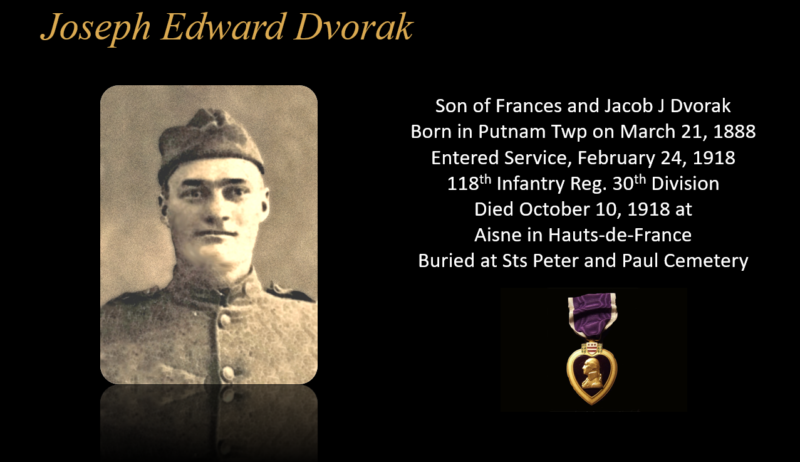

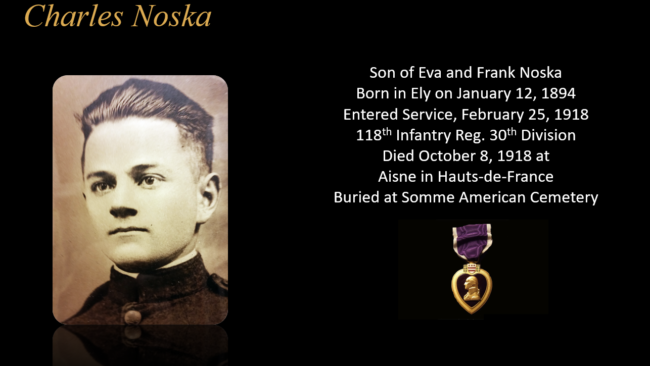

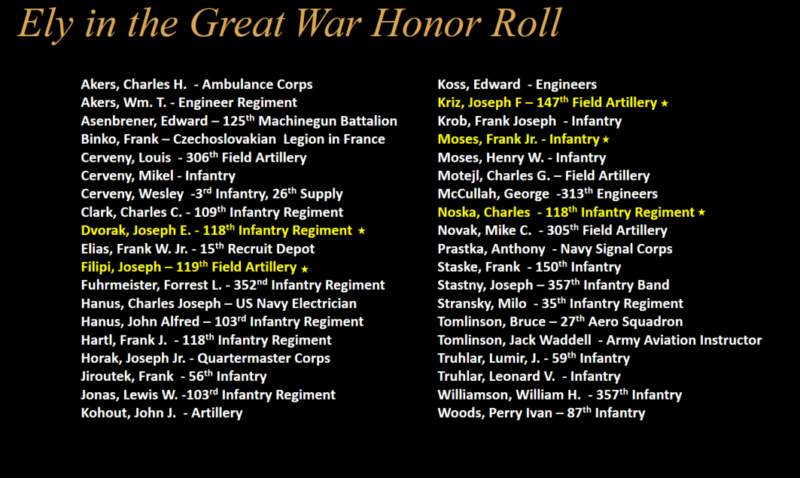

Two days later, on November 13, two sets of parents in Putnam Township received telegrams. The telegrams informed them of the deaths of their sons. Both men had been killed in France not far from the city of St. Quentin about five weeks prior. Those men were Joseph Dvorak and Charles Noska. Their sacrifice is the reason this post of the American Legion is named the St. Quentin Post.

It was obscure events in Europe that resulted in two farm boys from Ely making the ultimate sacrifice at a place called Brancourt-le-Grand in northeastern France.

In the summer of 1914, Joseph Edward Dvorak was 26 years old and still living with his folks on the farm. The Dvorak farm was located on Ivanhoe Road just west of where the Dows Observatory is today. He had attended classes at Cornell in Mt. Vernon and had served as a hired hand on various farms, but in the summer of ’14, he was back on the family farm with his parents and three brothers.

About a mile and a half south, at the intersection of two roads we now know as Hardscrabble and Seven Sisters, 20-year-old Charles Noska was also living the farm life. He and his twin brother Anton were the babies of the family, with three older brothers and two older sisters who had already left the farm.

In 1914, Joe and Charlie were probably preoccupied with threshing wheat or hoeing corn. They were likely interested the fact that Ely was being electrified. If they were baseball fans, they might have read that construction of Wrigley Field in Chicago was completed and was about to have its opening game. Maybe they read about a new rookie named Babe Ruth who looked promising. Perhaps they noticed that the Panama Canal was finally nearing completion and ready to open.

What they probably weren’t thinking about was Sarajevo.

Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina is a name right out of the headlines of the 1990s. In 1914, it had been annexed by Austria-Hungary. It was a multi-ethnic place even in 1914 and was populated by Serbs, Austrians and Muslim Bosniacs. It was a hotbed of strife that was a part of Austria-Hungary. It was about to be visited by the heir to the Austrian throne, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

In Sarajevo, a band of Serbian assassins of a group called ‘The Black Hand’ were waiting. This hapless group of students armed with dud grenades, cheap pistols and depleted arsenic tablets planned to kill the Archduke in the hopes that his death would, somehow, lead to Serbia assuming control of Bosnia.

At one point, one of the Serbs threw a grenade at the archduke’s car and missed only hurting bystanders. The assailant was quickly arrested and it looked like the assassination attempt was a failure. It wasn’t over yet, however. After a stop, the archduke was back on the road and his driver had made a wrong turn down a dead-end street. Blocked, he started backing up…

There, in a cafe, purely by coincidence and nothing more, sat Gavrilo Princip, one of the assassins. He had given up on the assassination and it is easy to imagine how shocked he was that the heir was suddenly there before him. He leapt to his feet, ran out and shot both the Archduke and his wife. They were both killed.

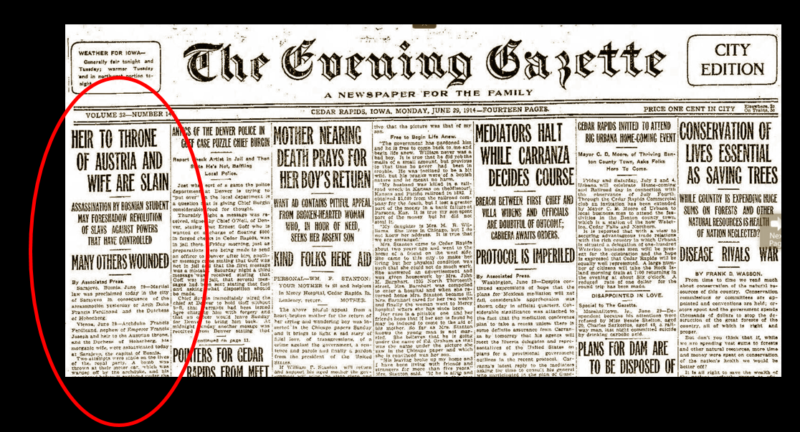

On Monday, June 29th, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette ran a small article with the title, “Heir to the throne of Austria and wife are slain.” The subtitle read, “Assassination by Bosnian student may foreshadow revolutions of Slavs against powers that have controlled.”

If they read the paper that day at all, it is easy to imagine Joe Dvorak and Charlie Noska completely ignoring an obscure column about the Austrian heir. They probably went straight to the baseball scores or other more interesting reading. After all, the 4th of July was coming and there were events everywhere and the newspaper that day foretold of the fun that was being planned.

It would have been impossible for them to imagine that the die had been cast. They couldn’t have known that events that would take them to combat in France had been set in motion.

In Vienna, the ministers of the Austrian government were shocked and angry. The emperor was called back from holiday.

It was quickly determined that Princip was a Serbian nationalist terrorist. The Austrians blamed Serbia for the assassination. People in both Austria and Germany were outraged. They demanded that Serbia be punished. On July 6, Germany granted their allies in Vienna a blank check to punish Serbia.

On July 23, a list of ten demands in the form of an ultimatum were sent from Vienna to the Serbian government. Serbia eventually accepted all the terms of the ultimatum except for the demand in Point 6: That Austrian police be allowed to operate in Serbia. The Austrians were furious at the rejection of even one of their demands.

At 11:00 a.m. on the 28th July, Austria declared war on Serbia. This time, the boys back in Iowa certainly noticed.

The Austrian declaration of war triggered a series of treaty actions. War declarations were made across Europe. Russia came to the defense of their fellow Slavs in Serbia and mobilized her military forces. Berlin declared war on Russia in defense of Austria-Hungary and on August 1, both Germany and France mobilized. On August 2, Germany declared war on Belgium. On August 3, Britain declared war on Germany.

On August 4, Germany invaded Belgium and the War to End all Wars began. A score of other nations also declared war.

Across the globe, enthusiasm for war was high. Church bells were rung and celebrations were held. Not everyone celebrated, however. In England, British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey remarked to a friend, “The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time”. He was more correct than he knew.

Back in Ely people were paying attention but most folks weren’t too worried. After all, President Wilson had promised to keep America out of the war. As part of a declaration to Congress that summer, the president said, “The United States must be neutral in fact, as well as in name, during these days that are to try men’s souls. We must be impartial in thought, as well as action, must put a curb upon our sentiments, as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another.”

Joe and Charlie, like most in the US, focused on the lives around them. They would have likely focused on farm work, baseball and girls. After all, the war was over there and they were safe over here.

Back in Europe, the German Kaiser had plans. Germany had long desired that the nation become a world power on par with Great Britain and war offered that opportunity. Germany went on the offensive.

The German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The German Army rolled though those nations and into France with little to stop them. The tide of the German advance, however, was blocked when French and British soldiers stopped the Germans at the Battle of the Marne in September.

At that point, both sides dug in along a meandering line of fortified trenches, stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss border. The war on the Western Front settled into a brutal, muddy, nightmarish slugfest of trenches, machineguns, artillery and gas warfare. Tens of thousands died. Hundreds of thousands were wounded or became ill. The stalemate lasted three years.

Back at home, despite the United States’ proclaimed a policy of neutrality and despite president Wilson’s insistence that Americans stay neutral in action and thought, the United States tended to favor Britain and France.

The clear majority of Americans wanted the United States to stay neutral. Of the minority who wanted war, virtually all favored siding with the allies. There was almost no support for America entering the war on the side of Germany. US banks supported the French and British war effort. US manufacturers sold war materials to Britain.

In May of 1915, the German U-boat U-20 sank the British liner Lusitania. There were 128 US citizens aboard almost all of whom died. Americans were infuriated but President Wilson said “America is too proud to fight” and demanded an end to attacks on passenger ships. Wilson warned the Germans that the US would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare.

Germany backed down said they would comply with his demand. By now, Joe and Charlie would have been paying a lot more attention to the war. The newspapers were running war related headlines daily. The sinking of the Lusitania aroused furious denunciations of German brutality.

Still attitudes were changing. A “preparedness” movement emerged. Its members argued that the United States needed to build up strong naval and land forces for defensive purposes. The assumption was that America would fight sooner or later. Some began calling for universal military service for young men. In response, a strong anti-war movement was growing as well, unleashing the fiercest battle in peacetime history over the military and foreign affairs.

None of this would have been lost on the people of Ely. Discussion in town was common. Those of German and Irish decent tended to demand America stay out of the war. Others were beginning to see war as inevitable.

Still, most favored neutrality. In 1916 Wilson was reelected president under the slogan, “He has kept us out of war.”

Battle continued to rage in Europe. 1916 saw the German failure at Verdun and its bitter withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line, its final reinforced defensive line in Belgium and France. The hellish Battle of Verdun broke the morale of French troops with mutinies and desertions a growing problem. British troops weren’t in much better shape.

Concurrent with the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line, the desperate Germans determined that unrestricted submarine warfare was essential to keep Britain from receiving war materials and sending them to France. They knew, however, U-boat attacks would enrage the United States and potentially bring them into the war. They had a plan.

The German Foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann invited Mexico to join the war as Germany’s ally against the United States. The communication From Germany to Mexico became known as the Zimmermann Telegram. In return for Mexico declaring war on the US, the Germans would send Mexico money and help them recover Mexico’s lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. British intelligence intercepted the telegram and passed the information on to Washington. Wilson released the Zimmerman note to the public on the 28th of February 1917. Americans saw the telegram and the German return to unrestricted submarine warfare as acts of war. Public demand for war grew.

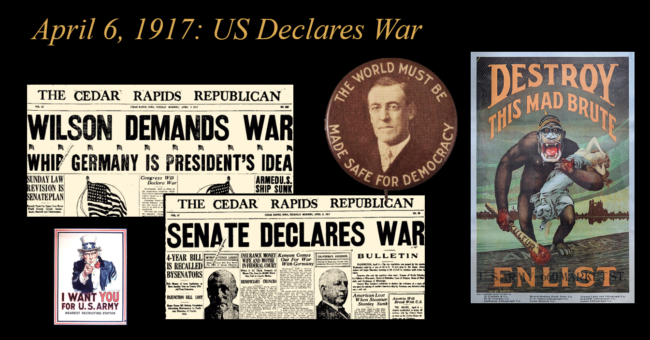

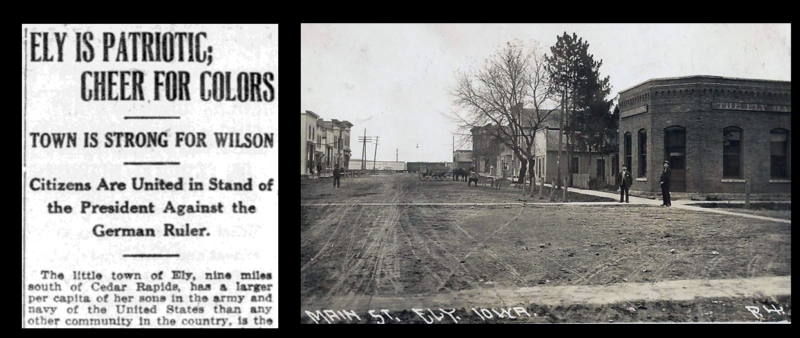

At first, Wilson tried to maintain neutrality. After submarines sank seven American merchant ships, Wilson finally went to Congress calling for a “war to end all wars” that would “make the world safe for democracy”. Congress declared war on Germany and its allies on April 6, 1917. The next day, on April 7, this article appeared in the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette.

‘ELY is PATRIOTIC; CHEER FOR COLORS; TOWN IS STRONG FOR WILSON

Citizens Are United in Stand of the President Against the German Ruler.

The little town of Ely, nine miles south of Cedar Rapids, has a larger per capita of her sons in the Army and Navy of the United States than any other community in the country, is the opinion of a leading resident of the village. Ely only has a population of 164, according to the latest census figures and it is said that nearly a dozen men of joined the national service in some branch in the last few years. Among those in the service at the present are Frank Horak, a sergeant in the regular army, Tony Praska, a wireless operator for the government and Charles Hanus who is serving his fourth term of enlistment in the Navy now being stationed on the battleship New Jersey.

Enthusiasm is high In Ely over the war situation and the town is unanimous in support of President Wilson. It is said there is only one German sympathizer within a radius of several miles of the town and that he has not been in town for three weeks, or since a traveling man took him to task for utterances against the United States Executive.

This enthusiasm was seen across the nation. Once war was declared, there was a complete mobilization of the entire population and the entire economy. The mobilization produced the soldiers, food supplies, munitions, and money needed to win the war. Rationing went into effect. Propaganda kicked into gear. War bonds were issued. After the passage of the Selective Service Act in 1917, the US drafted 4 million men into military service. On June 5, 1917, Joe Dvorak and Charlie Noska signed their Selective Service cards; both listing Putnam Township as their homes.

Once the Americans declared war, the Germans knew it was only a matter of time before a massive influx of fresh troops showed up in opposition. They believed that, with the U-boat war, it would take at least a year for the US to show up in France in force. In fact, the first US troops began to arrive in France in June. The American units did not enter the trenches in divisional strength, however, until October. It was in October that the Germans got some good news.

The Bolshevik Revolution effectively took Russia out of the war. By the spring of 1918, the Germans were able to move most of the men tied up fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front to France to face the allies. In total, 33 German divisions were released from the Eastern Front for deployment to the west.

With new manpower on the line the Germans had more men than the allies and the Germans launched the 1918 Spring Offensive. They called it the Kaiser-schlacht or Kaiser’s Battle. It was a new, last ditch offensive strategy to knock out the allies before the Americans were fully engaged. It began with huge attack against the British on the Somme to separate them from the French and drive them back to the channel ports. The attack combined new storm troop tactics with ground attack aircraft, tanks and a carefully planned artillery barrage that would include gas attacks. It was hugely successful… at first.

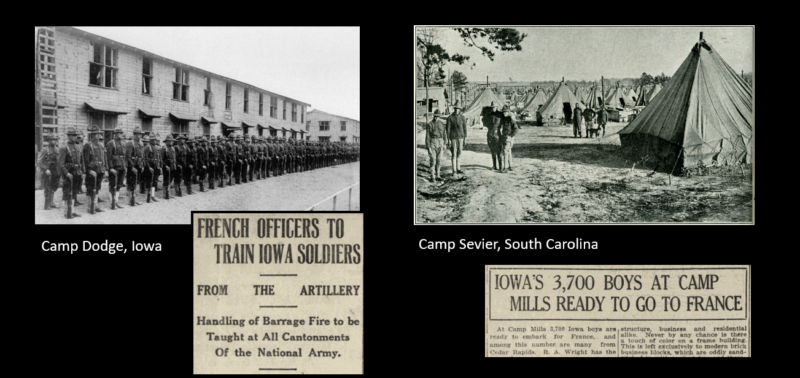

Back home in Marion, Joe and Charlie had been drafted and inducted into the Army in the last week of February of 1918. At Camp Dodge the boys were put into companies along with men from Minnesota and the Dakotas. They were eventually shipped to Camp Sevier in South Carolina where they were used to fill out the 118th Regiment of the 30th Infantry Division which was made up of men from South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee. The regiment’s war strength was 3,600 officers and men. Joe was assigned to A Company Charlie was assigned to H Company.

At Camp Sevier, the men were subjected long hours of training including drills, hikes, trench work and combat skills. They were taught the use of automatic rifles, machine guns, grenades and the bayonet. Their training was supervised by French and British officers who had experience against the Germans. The training was intense and the discipline was stern to the point of being nearly brutal. Tent living in cold and wet conditions had the troops fed up. They were ready to move on. On May 4th, they boarded trains for a four-day journey to Camp Mills on Long Island New York.

The boys were only a couple of days at Camp Mills when, on May 10th, they were ferried over to Hoboken where the boarded ocean transports for the trip across the Atlantic. On 11th, they set out on separate vessels all hidden from view below decks so any German spies in New York wouldn’t know the troop strength on board.

It was cramped and miserable journey that included at least one nasty storm and the constant danger of a submarine attack. They were escorted by British destroyers on the last part of the crossing and landed in Liverpool on the west coast of England on May 24th, 12 days after leaving the US.

They weren’t long at Liverpool. They were immediately packed like cordwood into a train eight to a berth that was meant for four. They were shipped overnight across England to Dover where they once again boarded transport ships. They crossed the English Channel and landed in Calais on May 27th, twenty-three days after breaking camp at Sevier. They were finally in France.

In France, the German Spring Offensive very nearly succeeded in driving the Allied armies apart and breaking through. The Germans advanced 40 miles during the first eight days and ultimately pushed the front lines more than 60 miles west. This was unheard of during the static trench fighting of the war to that point. The Germans were actually within shelling distance of Paris.

Because of the battle, the Allies agreed on unity of command. French General Ferdinand Foch was appointed commander of all Allied forces in France. The unified Allies were better able to respond to each of the German drives and the offensive turned into a battle of attrition.

The Germans had outrun their supply lines and suffered tens of thousands of casualties. The Kaiser’s Battle had run out of steam. Furthermore, the rapidly increasing American presence was counter balancing the large numbers of redeployed German forces. By the end of April, the German Spring Offensive had collapsed and the depleted German forces were, once again, falling back to the Hindenburg Line.

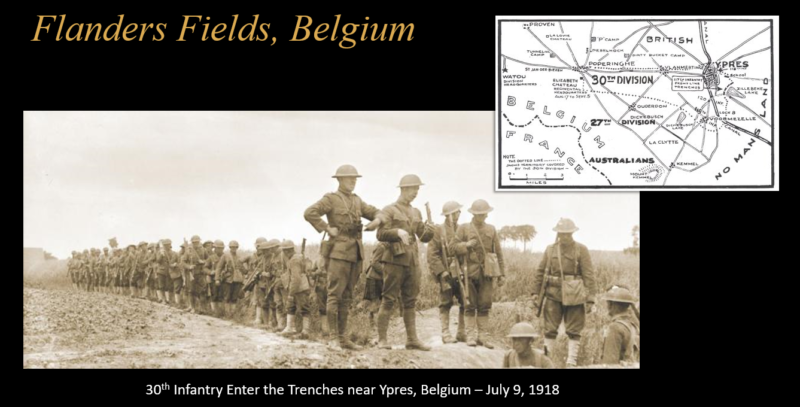

Back in the area of Calais, Joe and Charlie were discovering what life was like in a war-torn country. They found themselves billeted in barns with rats and lice for companions. Rats served as target practice and the cooties served nothing but discomfort. Regular training was again part of their daily routine under the control and supervision of the 2nd British Army. The entire regiment was outfitted with British rifles and equipment. They only retained their American uniforms and packs. On July 2nd, they finally decamped and started a three-day march into Belgium.

In April, the Germans had attacked in Belgium as part of the Spring Offensive with the objective of capturing Ypres. Their goal was forcing the British forces back to the channel ports and out of the war.

As with the rest of the Kaiser’s Battle, it was a failure. The 118th Regiment was assigned to the area of Ypres to fill in for exhausted and depleted British troops. Joe and Charlie took part in 50 mile hike from the French Department of Calais to Belgium. It was a brutal march with heavy packs, the last few miles under occasional German shell fire. On the 4th of July 1918, the 118th crossed into Belgium, the first American regiment to enter that devastated country. They staggered into a place called ‘Dirty Bucket Camp’ on the Ypres Salient.

In Belgium, US troops were shocked by the difference in morale between British and Belgian troops and the green US troops. US troops were full of enthusiasm and confidence. The veterans of the Great War, however, were definitely not looking forward to further combat. The Americans took their place in the trenches.

Things were relatively quiet in Belgium. It would have been hard to believe that some of the fiercest fighting of the war occurred in the area where they were camped. The horrifying, murderous Battles of Flanders took place in the area. In fact, the poppies of Veterans Day are memorial to the battles that took place on Flanders’ fields. That wasn’t the case in the summer of 1918, however. The expected great German drive on the Channel Ports failed to materialize. Other than a few stray artillery attacks, the boys didn’t see much fighting in Belgium. On September 6th, after two months in Belgium, Joe, Charlie and the men of the 118th Regiment marched back to France.

In France, the German front line was broken at the Battle of Amiens and Allied forces were advancing. Australian forces crossed the Somme River on the night of 31 August, breaking the German lines during the Battle of Mont Saint-Quentin. The French First Army neared the Hindenburg Line on the outskirts of St. Quentin during the Battle of Savy-Dallon. The British Fourth Army approached the Hindenburg Line along the St Quentin Canal, during combat on 18 September. The Germans had been forced back close to the Hindenburg Line and they were at the breaking point.

Joe and Charlie were stationed in reserve near Amiens and were being trained in mobile assault tactics. That lasted until September 22nd when they began the journey that would carry them to the Hindenburg Line a few miles north of St. Quentin. They were moved by trucks through the terrible devastation of the Somme Battlefield. The effects of four years of combat was utter ruin. They saw flattened villages, devastated farms and miles and miles of rusty barbed wire, trenches and shell holes. Finally, they arrived at a line a mile west of the village of Bellicourt and the Hindenburg Line.

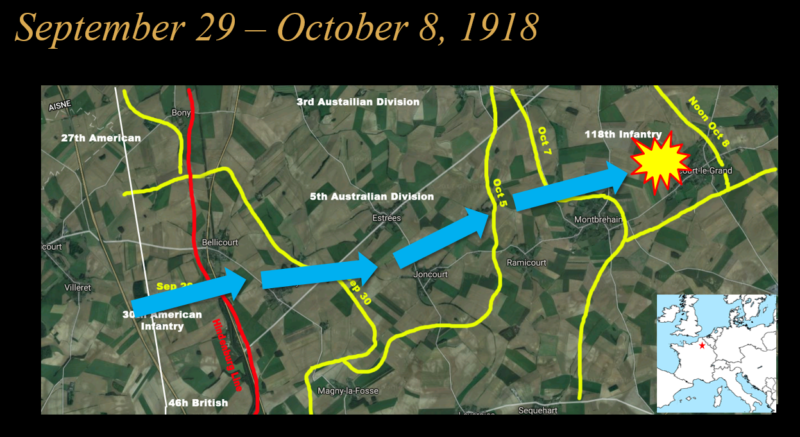

The 118th was part of the 30th Division. To its left was the American 27th Division. Both divisions were placed under Australian Command under Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash as part of the British Expeditionary Force.

Australian troops had been serving in hard combat for years. Their ranks were depleted and they were near the breaking point. They had suffered such heavy casualties that companies of Americans could replace entire battalions of Australians. Americans of the 118th took their first casualties from enemy artillery fire. Joe was slightly wounded by shrapnel on September 28th. He was back in the trenches in no time.

The men began the process of working to secure their positions under harassing German machinegun and artillery fire. Skirmishes took place and men died in twos and threes. On the 25th, the 118th 1st Battalion commander was severely wounded by shell fragments. The war was real now. Ahead of them was the supposedly impregnable Hindenburg Line and they were going to attempt to break it.

The position held by the enemy was not only strong, it had a few unique features. The defensive line was begun in 1914 and constantly improved since then and formed one of the strongest points on the Hindenburg Line. In addition to several belts of razor wire and a complete trench system, it had the natural obstacle in the St. Quentin Canal. This made the line as impregnable as humanly possible.

The Canal was over a hundred years old and was in a deep ditch. At Bellicourt, the canal passed through a four-mile-long tunnel. The ditch and the ground above the tunnel were protected with double apron barbed wire that seemed to withstand all artillery fire. The tunnel was filled with barges and formed an absolutely, positively impregnable bunker system. The 118th was to be the first unit of the American Expeditionary Force to throw itself against the Hindenburg Line. This where they did it.

On the morning of September 29th, the 27th and the 30th Divisions, including the Joe and Charlie in the 118th, attacked the Hindenburg Line. The battle was preceded by the greatest British artillery bombardment of the war. Some 1,600 guns were deployed firing almost one million shells over a comparatively short period of time. Included in these were more than 30,000 mustard gas shells. These were specifically targeted at headquarters and groups of batteries.

As the 30th American Division and then Australian 5th Division moved forward, the units to their left did not. They had to contend with German fire from the side and rear as well as from ahead. An added difficulty was thick fog across the battlefield in the earlier stages of the attack. This led to American troops passing by Germans without realizing that they were there, with the Germans causing severe problems to the Americans. Fog also caused problems for infantry/tank cooperation.

Still, the 30th Infantry Division broke through the Hindenburg Line in the fog on 29 September 1918, entering Bellicourt, capturing the southern entrance of Bellicourt Tunnel.

The Americans paid a terrible price in casualties in breaking the line. More than 13,000 were killed or wounded. General Pershing, wrote: “… the 30th Division did especially well. It broke through the Hindenburg Line on its entire front and took Bellicourt and part of Nauroy by noon of the 29th.”

The Australian commander of the attack wasn’t as sure. Regarding the green American troops under his command, General Monash wrote: “…in this battle they demonstrated their inexperience in war, and their ignorance of some of the elementary methods of fighting employed on the French front. For these shortcomings they paid a heavy price. Their sacrifices, nevertheless, contributed quite definitely to the success of the day’s operations.”

In retrospect, it is easy to believe that troops who had never served in combat would not perform as well as hardened veterans. They were green troops but their courage can never be doubted.

On the right of the tunnel, the British 46th Division saw an astounding success. They cut the heavily defended ditch in an amazing military feat, crossed the canal and met all their objectives. They even managed to seize the still-intact Riqueval Bridge over the canal before the Germans had a chance to fire their explosive charges they had set.

It was September 29th, the day of the Battle of St. Quentin Canal, that German commanders Eric von Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg first told the Kaiser the war could not be won and that they must have an immediate armistice. The war, however, continued.

Joe and Charlie were now occupying former German trenches holding the line east of the canal. They supported continuing attacks from October 3 to October 8 in which US, British and Australian troops captured Montbrehain on October 5 and the village of Beaurevoir on October 5 and 6. This resulted in a total break in the Hindenburg Line. On October 8, the 118th – including Joe and Charlie – would be called to form the spear-point for the attack on the German salient emanating from the village of Brancourt-le-Grand.

At ten minutes past five, the assault began as artillery laid down a heavy barrage and the men went “over the top”; slang for leaving the trenches and charging into no-man’s-land. They followed tanks into the attack.

It was a beautiful morning, not cool or hot and the mist cleared allowing the men to keep in contact. At first, they made good progress toward Brancourt. The enemy, however, began to hit the regiment with machine gun fire and heavy artillery. The regiment began to suffer very severe casualties. Several officers were killed and wounded. A company of the 120th Infantry that had been sent forward was caught in a barrage on the edge of Brancourt with terrible results. One platoon lost every man.

Combat for the 118th was intense but there were acts of great heroism in the regiment. Three men from the unit earned the Medal of Honor that morning.

It was during this morning’s fighting that Joe and Charlie fell. Joe, was with a group of six who were advancing on the field when hit by shrapnel from artillery fire. Three were killed immediately. Joe and two others were wounded and carried off the battlefield. Joe died at an aid station on October 10. A fellow member of the 118th, Frank Hartl, a founding member of the St. Quentin Post of the American Legion, witnessed Joe fall that morning. Hartl was wounded in the same engagement.

The circumstances of Charlie’s death are a little less clear. A telegram from his lieutenant to his mother said he was killed on the battlefield that morning. His official military record, however, said he died of his wounds five days later on the 13th. Charlie’s parents said he was killed on the 8th in a newspaper article three years later. The testimony of his platoon leader and parents over military records are convincing. It seems evident he was killed on the morning of October 8th.

Both men were temporarily buried in Tincourt, France; north of St. Quentin.

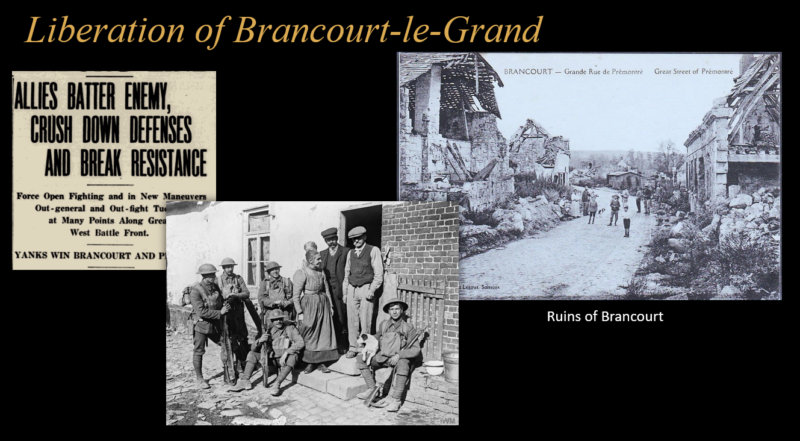

By noon, Brancourt was captured. The line had been advanced over three miles, 766 prisoners were captured including 16 officers and a vast amount of enemy material was captured. The taking of Brancourt resulted in the liberation of the few remaining civilians who were still there after four years of German occupation. An American witness said it was “impossible to describe the amazement and joy of these poor people when they realized that the enemy had been driven from the village. No more pathetic scene can be imagined than that enacted by them when they crawled out of their cellars to find that Hun rule was a thing of the past. It was here that we first saw evidence of the barbarous treatment by the Hun of those who had been forced to live under his iron rule.”

By noon, Brancourt was captured. The line had been advanced over three miles, 766 prisoners were captured including 16 officers and a vast amount of enemy material was captured. The taking of Brancourt resulted in the liberation of the few remaining civilians who were still there after four years of German occupation. An American witness said it was “impossible to describe the amazement and joy of these poor people when they realized that the enemy had been driven from the village. No more pathetic scene can be imagined than that enacted by them when they crawled out of their cellars to find that Hun rule was a thing of the past. It was here that we first saw evidence of the barbarous treatment by the Hun of those who had been forced to live under his iron rule.”

Today, there is a monument to the men of the 118th in Brancourt-le-Grand celebrating their heroic effort.

The 118th occupied the line at Brancourt for two days and three nights. It went on the offensive again on the mornings of the 11th and 17th and followed in close reserve on the 10th, 18th and 19th. On the 24th of October the regiment was withdrawn to the Heilly Training Area near Ameins.

The German were in a rout, their supply lines collapsed, morale was broken and, back in Germany, revolution had broken out across the land. The Germans knew they were facing total defeat. They asked for an armistice that became a virtual unconditional surrender. The Kaiser was run from Germany into exile. In Austria, the emperor was overthrown. The Russian empire had collapsed in 1917. The map of Europe was about to change.

On the night of November 11 news of the Armistice reached the men, much to their relief.

The coming months were not to be easy for the men of the American Expeditionary Force, however. The men of the 118th Regiment, for example, did not ship for home until the following March and the intervening period was one of terrible boredom, poor living conditions and only sporadic pay.

Across France, hundreds of thousands of impatient draftees found themselves trapped overseas and pining for home. They all knew that untold weeks or months lay ahead of them before their return would be logistically possible. A suggestion was made that a new servicemen’s organization be created to serve the needs of the members of the expeditionary force. General Pershing issued orders to create an organization and set of laws to curb the problem of declining morale. From this order the American Legion was born.

Back at home November 11th brought great joy and relief to the parents of Joe and Charlie. The war had ended. Sadly, their joy was short lived. Two days later they each received telegrams informing them their sons had been killed in France. It must have been devastating.

Up through the first years of the Civil War, those killed in combat were usually tossed in a mass grave and that was that. Later in the war, the creation of Arlington National Cemetery led to many battlefield cemeteries. The fallen were buried with honor near where they fell. Plans were made in France to continue this tradition.

American mothers, however, had other ideas. Many wanted their sons’ remains brought home. This thought did not appeal to the government of France, however. The thought of the grisly job of disinterring the remains and shipping them across the land to transport ships was not something they wanted to consider. They denied the request.

American mothers persisted, however and, with American diplomatic effort, the French eventually gave in. The War Department sent letters to next of kin asking whether they wanted their sons’ remains buried in American cemeteries in the land they fought to defend or if they wanted them returned to the US. About 60 percent opted to have the remains returned home.

Charles Noska was disinterred and reburied in the Somme American Cemetery in Bony France. His grave is located about seven miles from where he fell in battle and is beautifully and meticulously maintained in a peaceful and patriotic setting.

Joseph Dvorak’s parents opted to have his remains returned and, three years after he fell, they were reburied in Saints Peter and Paul Cemetary near Solon. About 1,500 people attended his 1921 funeral including all members of the newly formed St. Quentin Post of the American Legion.

World War I was a war over very little of consequence and yet its effects were of huge consequence. The war resulted in an explosion of nationalism across Europe and the world. It unleased both fascism and bolshevism. The imperfect peace of November 11 gave us the even more nightmarish World War II. That war didn’t end it however. It led to the Cold War; the remnants of which are still being played out in places like North Korea. The obscure events of Sarajevo in the summer of 1914 haunt us yet today.

Another reason to remember, of course, is to honor those who left home and hearth and traveled across the globe to defend that which deserved defending. To quote Abraham Lincoln, “from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion”. It is important to remember those from Ely who gave that last full measure in France in 1918

Joseph Dvorak, fell in October 1918 near the village of Brancourt-le-Grand and the city of St. Quentin, France.

Charles Noska, fell in October 1918 near the village of Brancourt-le-Grand and the city of St. Quentin, France.

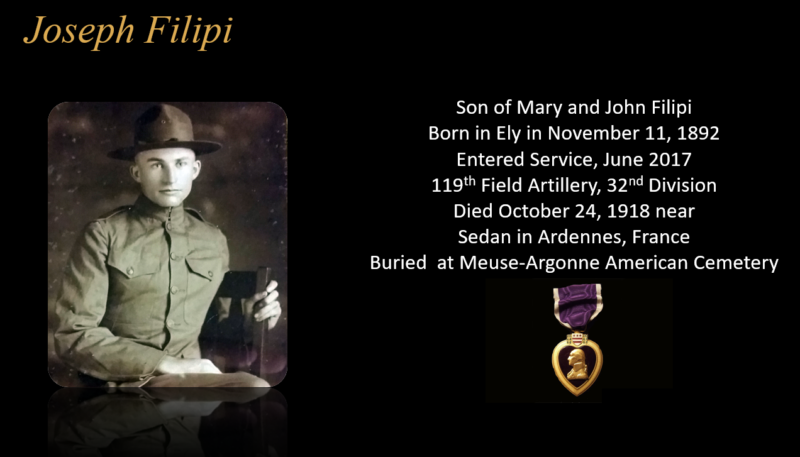

Joseph Filipi, fell in October 1918 near Sedan in Ardennes, France.

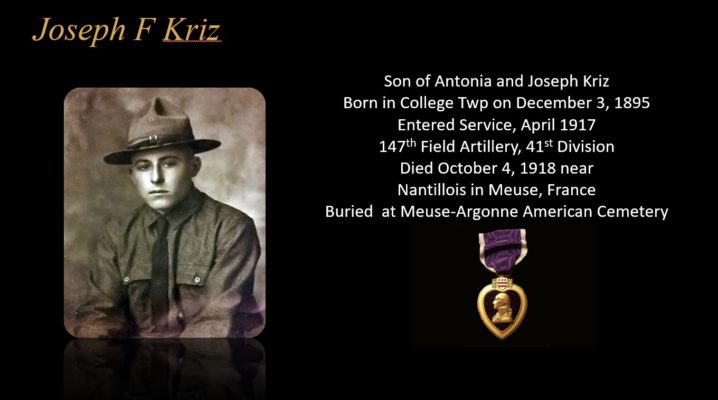

Joseph Kriz, fell near Nantillois in Meuse, France.

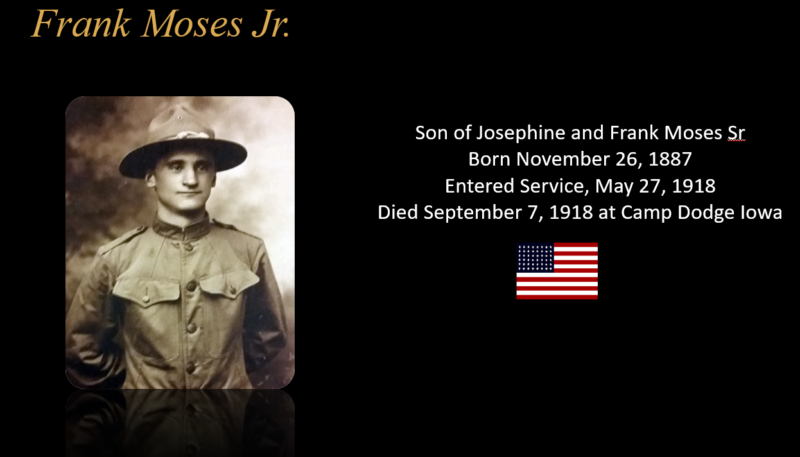

Frank Moses, died in May 1918 at Camp Dodge Iowa.

And all of those from Ely who served in the Great War.

The sentiment of Lincoln’s address was also captured in a poem written in 1915 among the poppies fields of Flanders.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.